The Body as a Book

A reflection on the practice of performance, 2010

I see the body as a book in which I can learn to read the connections with the self, and with the immediate and the cosmic environments. I use what I read to articulate a performative language that involves dancing, choreographing, and teaching.

I made my first professional appearance in a solo called Iritis in 1979. This solo was the result of a process integrating various dance techniques including the study of Baratha Natyam (South Indian Classical Dance).

The Baratha Natyam technique is deeply embedded in spatial concepts related to the architecture of Hindu temples. This lead me to study architecture and engage in projects based on various modern works of architecture including a study of the Villa Savoye of La Corbusier. At the Villa Savoye I carried out a “Body Survey” with my own body, performers and architecture students. Indian Dance also attracted me because of its codified movement-language that is also part of a larger cosmology. From this I developed an understanding of movement that had no frontal perspective and fully engaged the body by questioning how does movement happens, what language does it create in the dynamics of our environment.

Initially my overall approach was very formal because I was, basically, exuberant, afraid and over-energized and I needed a complex form to channel my states. I needed this complexity to harness this incredible force and rage of movement and to relate it to something larger than myself and to inform me about my connection with all that was around me in an immediate and absolute way. By ‘immediate’ I mean ‘here and now’, and by ‘absolute’ I mean ‘laws of nature and cosmos’.

The complexity of Baratha Natyam was a way for me to learn different layers of an approach to dance as integrative and all-inclusive, as it obliges a dancer to let go of the self in order to let the body become a vector. I saw that architecture and dance have the same requirements. An architect has an obligation to materially manifest the basic notions of light, movement, stability, temperature, acoustics, orientation, concentration, living and organic functions and so on. In its structure, a building has the same laws that any ‘living’ body has. And a body-in-motion is the ideal medium for revealing the interdependence of buildings and body.

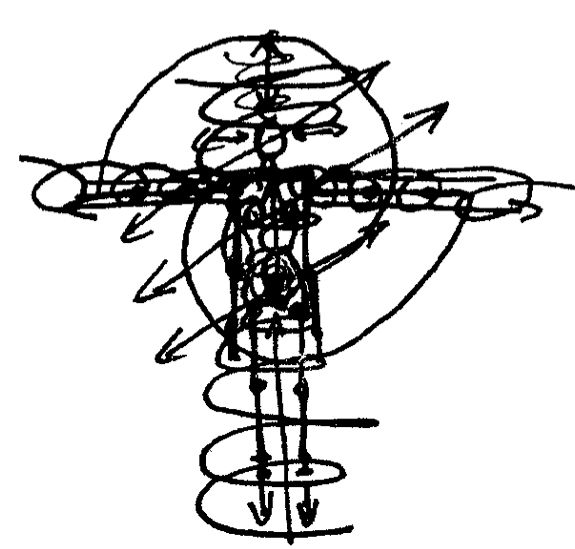

While studying Baratha Natyam and architecture, I realized that the most important aspect of artwork is the creation of possibilities—by creating correspondences within the body itself, and then between body, the mind and my environment. At this point I declared that my work was a Space of All Possibilities. The moment that movement manifests also marks the inception of our intention and the materialization of its expression. Just before inception everything is possible. The course of my work became the exploration of ways of never disconnecting from All Possibilities—of tapping into IT at any instant.

As is the case for most dancers, injury and facing pain played a very important role in my exploration of dance and performance. Injuries become teachers. Often when the body opens it hurts—it can hurt physically, emotionally and spiritually. Part of creating possibilities involves the recognition of patterns within us that are obstructive to the core body and then letting them go. Such de-patterning stops interferences within All Possibilities. My injuries forced me to ask myself how movement occurs. Adding to this obsession with injury my enquiries into the interrelationships between behavior and architecture and the body and universal forces, I gradually gravitated toward a body/mind symbiosis strengthened by the Alexander Technique and intensive study of neuroscience. With Chi Kung, and the Chinese Five Elements Theory I started a journey toward an understanding of how energy and matter are one and in constant transformation, and how we, with our organs/senses/emotions/orientation and the connection with the elements, are agents of this transformation within us and without. The key to the performance approach that I have developed is based on an active breakdown of the dynamics at play within us within our environment. Though my practice allows me to immediately engage my world in extremely practical and helpful ways, I have now and them, nonetheless, been classified as a ‘mystic” artist. If mysticism is movement toward the hidden and inexplicable that calls for a commitment to discipline, endless curiosity and scientific method, then yes I would call myself a “mystic”.

Chinese medicine says that is it the sprit that gets sick before the body. This has immense implications in the understanding of economics, politics, emotions, psychology and art. This statement grounds us, gives us a constant reality check that takes us beyond what we think is happening and opens up a space of freedom and spontaneous solution. I pursue this because it gives me profound happiness and infuses me with the ability to listen deeply to others.

I think it is essential to have a discipline that helps you to sustain your work physically, emotionally and spiritually. Therefore I named this approach THE INNER STRUCTURE OF ‘THE BODY’ or ‘cultivating possibilities’. There are many ways to understand how the body can be strengthened (and why we want to strengthen it). I try to orient us around the idea that the inner structure is a conduit for energy. Understanding and cultivating this channeling allows us to optimize energetic and creative possibilities in performance.

In performance, there is an archaic expectation that heroism will arise—a heroism that would take us beyond the limitations of the body. Whatever performance has become, it is still rooted in ritual. It’s something acted out in a social context to address, reveal, or sublimate the human condition. Whether it looks like a dancer is “giving birth to a cube” (as one dance critic said of M. Graham), or whether a dancer has anatomically accomplished what was imagined on a computer (as Merce Cunningham had done), performance is about heroism. or for example in Jerome Bel’s Veronique Doisneau, revealing a member of the corps de ballet as a soloist a lone on the Paris Opera stage, speaking about her career and dancing Swan Lake, as she is about to retire – it is about heroism; or in a complete different way with Steve Paxton extending the individual into the collective with Contact Improvisation. In still, there is the heroism of taking us beyond the limitations of body, individual and ego. In western countries, performing arts need to create a body that is ‘missing’. The impulse is to respond to the current way in which the body is being lived. For example, in a world of mass production and over stimulation, the tendency could easily be toward stillness and the stationary. In an intensely puritan time, the tendency may be toward the sexually charged and licentious. It’s a very reactionary process.

The body is a vehicle for the performer to express what she or he foresees as a necessity to create. A performance-maker chooses the complexity of the layers through which the performance will be revealed. The further ancient performance forms are the more layers are found and heroism is also about the mastering of the codification where contemporary heroism is often about erasing layers to find directness of the expression as if a subject is always to be more of what it is. I believe this is why in some level the idea of ritual can be perceived as “ridicule” to our times for some people since ritual are to peal of the self as a the subject.

Traditional forms of performance were teachings wherein the audience could learn about being a god, a hero, or a demon. This required transcendence. The elements of the performance entirely transformed what a ‘human’ would look like. This transcendence made people look beyond human or other than human. This is how ‘human’ learned about humanity (what it is to be human...by positing near-human). The codes were complex enough to remain mysterious, while being familiar enough to integrate the action with the social landscape. The question of “realness” was skewed in order to see more vividly (to show what was not ordinarily viewable).

This heroism was transmitted to an audience by way of kenosis: emptying as liberation. It required self-dispossession. Such dispossession is rather paradoxical for a performer must have wanted, initially, to appear on stage (as distinct from using the stage to lose identity). To accomplish the desire to appear on stage, the performer must let go of oneself for the language of performance to be alive—and therein lies the paradox. In the traditional Indian dance/theater form known as Katakali, before performing the performer has to empty himself from his body and invoke the god, demon or hero he intends to embody, only to empty himself of the character at the end of the performance and invoke his own person once again.

In the life of contemporary Western performance, usually there is a split between two different processes happening simultaneously within the performance-maker. It is as if the ‘body’ divides to become the body that performs the dramatic vision and the body that goes through the process of transformation to create that projected body. The body that is being transformed is often mixed up with the performer’s personal life and evolution as a human being. What gets performed gets performed through our experiences of ourselves, regardless whether we are aware or unaware of any pathologies we might be carrying along. As one of my teachers has said: “We have pathologized the demons”. There is no judgment in this statement—great art has been made this way as well (when pathology has become the creative motor). In Ancient Greek and Asian forms of performance the techniques that support the ‘making’ of the performance are integrated in a cosmology wherein the physical and the spiritual are in sync with each other. Looking at the body from the perspective of western medicine we see a completely fragmented body. If neuroscience is such a predominant paradigm right now it is because it's morphing into neuropsychoimmunoendocrinology. The necessity to reassemble a body as a whole and not as exploded parts is expressed in many fields of research. This necessity asks us to go beyond the market-oriented “mechanical body” that locks us into limited energy and limited understanding of who we are.

We have to create a “mechanical performing self” where the emptying or kenosis must predominate if we are serious about creating new possibilities. Because the relevance of art is now relevant to humankind in peril, art is more relevant than ever. Are we here to reveal the unseen and to foresee what we could do as artists and humans for the benefit of all creatures, or are we merely having a discourse about the relevance of NOW in relation to the survival of our art sector?

It’s essential to look at performance from the perspective of being bold and seriously active in bringing out all the potential of being alive relative to all beings.

Hyper-specialization has fragmented western culture; and attempts to put Humpty Dumpty back together again often look at the picture one element after another element after another element, instead of focusing on the layering of the understanding of how our organism works as a whole in a mutual entanglement with our environment (as the recent science of epigenetics emphasizes) . The purpose of this writing is not to address ecology in itself, but to arduously look at the art of performance and see how can we relate, through performance, to ecology and economics and the ethos of our culture as a whole, determining who is being effected, who is benefiting from our efforts as performers and to come up with ways in which we can be working together toward desired ends.

Soma in Greek means body or living body – how did somatic works (Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais, BMC …) become something separate from the creative works of performance-making? Certainly in Greece in the first millennium BC, individual development and solitary healing in darkness was powerfully correlated with public performance and theater. In the sanitariums of Asklepios, a ‘patient’ could experience both isolation (in a chamber called an ‘abaton’—place of retreat in the dark), and public catharsis in an amphitheater.

In the art of tragedy in ancient Greece, words, music, and dance were completely integrated as one art form. (Even poetry and dance together formed a proper genre known as choropoieia.) The ‘actor” was called the hypocrite. ‘Hypocrite literally means: under crisis, (crisis meaning separation),thus: the one who embodies separation. We can then ask: What is this separation? It is the separation between the mind and body? There is a blank between mind and body and in that blank lies the possibility of accessing infinite connectivity beyond the selfwhere everything can converge. This catharsis or cleansing happens by letting the audience experience the sublimation of the interference and fragmentation that exists within consciousness as a unified experience of self, other and environment. The observation of the breaking down of this unity creates the cathartic experience for the audience that is made whole (made into one social body) by going through the cathartic experience together.

Let’s create the tools with which we can sustain these questions within our works. It’s an everyday practice through which performance takes place in return to remind us that we should keep asking the questions, as the questions are the matter of our becomings.

Excerpt of The Art of the Heart from chapter 49 of Guan Zi.

Can you concentrate?

Can you adhere to the unity of nature?

When the four parts of the body have become corrected and the Blood and Breaths have become quiescent,

You may make your intellect adhere to the unity of nature and concentrate your Heart...

It is ever so that the life of a man must depend on imperturbability and correctness.

The way in which they are lost is certain to be through joy or anger, sorrow and suffering.

For this reason,

To put a stop to anger there is nothing better than poetry.

For getting rid of sorrow there is nothing better than music.

For moderating music there is nothing better than the rites.

For preserving the rites, there is nothing better than respect.

For preserving respect there is nothing better than quiescence.